Nick Chater’s Mind Is Flat challenges several core common-sense notions and beliefs about the nature of our minds and even who we are as cognitive beings. Specifically, the book argues against the idea of a deep subconscious (like an inner self or ego) and presents a novel view of how the mind works.

Chater’s central critique is that we do not possess a mind with hidden depths nor do we possess profound beliefs, desires, and emotions. Instead, he posits that our minds and selves are ‘constructed on the fly,’ manifesting moment by moment as improvisations influenced by past experiences and the present context. Our brains are dynamic improvisors. He labels this alternative view as a “flat” model of the mind.

Chater encapsulates this concept succinctly:

“In this book, I want to convince you that the mind is flat: that the very idea of mental depth is an illusion. The mind is, instead, a consummate improviser, inventing actions, and beliefs and desires to explain those actions, with wonderful fluidity. But these momentary inventions are flimsy, fragmented and self-contradictory; they are like a film set, seeming solid when viewed through the camera, but constructed from cardboard.” (p 9)

This book is profoundly important for anyone who seeks greater self-understanding and believes our brains plays tricks on us worth knowing a bit more about.

Here are my key takeaways and lessons as well as a selection of book notes.

My Quick Take Book Review

- ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ I rated this book a 5 out of 5 on Goodreads.

- Would I recommend it? Definitely, I’d recommend this book to science-minded folks seeking an alternative, brain-centered perspective on how we are and how we experience the world.

- Would I read it again? Unlikely, though I’ll definitely re-look at parts of this book again as I continue readings on the brain and the self.

What I got out of this book?

Chater leverages research from various fields like psychology, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence to critique the idea of hidden mental depths and demonstrate how our brains create meaning sequentially and how our perception of the world is far less rich than we believe.

Among the key lessons I took from the book are the following insights:

Illusion of Depth: “There are no mental depths to plumb.”

What if the surface is all that there is and we merely use our imagine to conjure depth?

One of the most important and initially counterintuitive ideas found in the book is called the “illusion of explanatory depth.” This refers to the phenomenon where people feel they deeply understand something (“I know this deep down”) but struggle to provide coherent explanations when asked.

This phenomenon is especially common in how people overestimate their understanding of complex systems, like how a product experience or business model work. We often assume and justify a deeper understanding based on certain simplified data or generalizations.

“The sense that behaviour is merely the surface of a vast sea, immeasurably deep and teeming with inner motives, beliefs and desires whose power we can barely sense is a conjuring trick played by our own minds. The truth is not that the depths are empty, or even shallow, but that the surface is all there is.” (p 8)

Popular culture, psychoanalysis, etc all imagine that we and our minds possess hidden depths of belief, motive, and subconscious thought. We might even go so far as to label this as a belief in an intangible and everlasting “soul.” To quote:

“No amount of therapy, dream analysis, word association, experiment or brain-scanning can recover a person’s ‘true motives’, not because they are difficult to find, but because there is nothing to find. It is not hard to plumb our mental depths because they are so deep and so murky, but because there are no mental depths to plumb.”

Chater argues that instead our cognitive activity functions as a flat, improvisational system. According to him, the sense of mental depth is an illusion—a “conjuring trick” of the brain. Rather than plumbing an inner world of pre-existing truths, we generate interpretations and justifications in the moment, much like creating a fictional narrative.

Kuleshov Effect and Contextual Perception

Is what you are seeing, feeling, or thinking tied to a recent event or context?

Named after Russian director Lev Kuleshov, the Kuleshov effect is a cinematic technique that demonstrates how the interpretation of an ambiguous facial expression can be dramatically altered by the context in which it is presented.

Using the same shot of a relatively impassive face of Russian silent film star Ivan Mozzhukhin, Kuleshov intercut the scene with three different images: a dead child in an open coffin, a bowl of soup, and a glamorous young woman reclining on a divan.

Curiously, audiences were impressed by what they perceived as Mozzhukhin’s subtle acting, interpreting his expression as grief when shown with the coffin, hunger with the soup, and lust with the reclining woman. However, the shot of his face remained the same; it was the context of the other images that changed the meaning. This demonstrates that viewers project their own interpretations of emotion onto the face, based on the context provided.

Outside of film, another study used a photo of a US senator at a campaign rally that could either look angry and frustrated when the context of the rally is removed or happy and triumphant within the context of the rally. In this case, the background of a still photograph can also dramatically alter how we “read” a face emotionally.

The Kuleshov effect provides evidence that our emotions are not inherent or pre-existing states within us, but rather are constructed through interpretation. The meaning we derive from expressions or situations is dependent on context. It is similar to how the brain interprets an ambiguous image, like the duck-rabbit, based on its surroundings.

In short, the brain is always looking for the most meaningful interpretation of the available information and that process is heavily influenced by the surrounding context. Likely this “flaw” extends to the limitation in our self-interpretation of our mind’s emotions too.

Just as viewers project meaning onto a character’s expression, we construct interpretations of our own physiological states—like a racing heart or adrenaline surge—based on situational cues, reinforcing the mind’s improvisational nature.

[Summary] Book’s Big Ideas: The Mind is Flat

- The mind as an improviser: The mind is not a container of pre-existing beliefs and desires, but a “consummate improviser” that invents actions, beliefs, and desires to explain those actions. This improvisation is fluid, but the inventions are often flimsy, fragmented, and self-contradictory. The mind is constantly interpreting, justifying, and making sense of behavior in the moment.

- The “interpreter”: The language-processing system in the left hemisphere of the brain is called the “interpreter” and it “invents” stories about why we do what we do. It is a master of speculation and can have no insight into the origin of choices but invents explanations anyway.

- The mind as an impossible object: The mind only has the superficial appearance of solidity. Like impossible objects created by artists, our minds have contradictions and gaps.

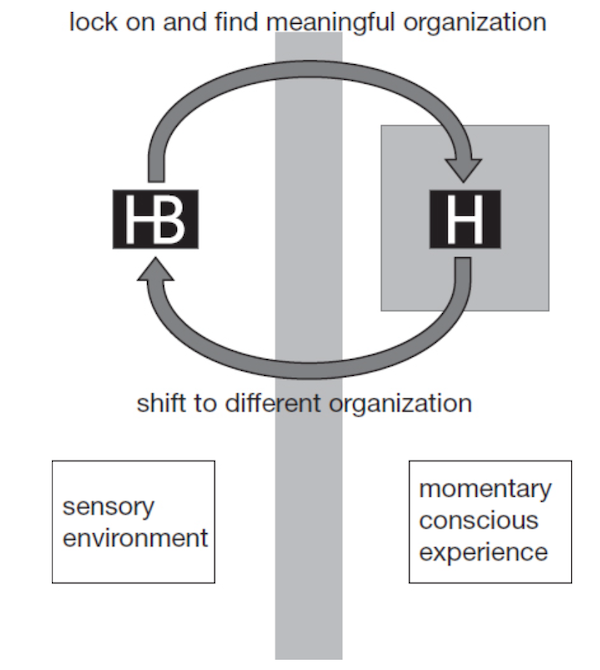

[Model/Schematic] Cycle of Thought

How does the mind transform fragmentary sensory input into coherent interpretations and meaning?

“Conscious experience is therefore the sequence of outputs of a cycle of thought, locking onto, and imposing meaning on, aspects of the sensory world. That is, we consciously experience the meaningful interpretations of the world that our brain creates, seeing words, objects and faces, and hearing voices, tunes or sirens. But we are never conscious either of the inputs to each mental step or each step’s internal workings.” (p 12)

Chater describes the brain’s continuous engagement in making sense of sensory input through what he terms the cycle of thought. Consciousness, and thought, appear to be guided sequentially through a narrow bottleneck, with deep, sub-cortical structures searching for patterns in sensory input, memory, and motor output, one at a time. It is during a cycle of thought where the brain creates a meaningful organization of sensory input (or meaningful from disparate thoughts and ideas).

Schemetic/Model

“Our brains are, then, relentless and compelling improvisers, creating the mind, moment by moment.” p 217

Chater provides the following schematic:

Consciousness operates as a sequence of momentary interpretations of sensory input. This diagram illustrates how the mind shifts between sensory inputs from environment (or even your own memories) and creating interpretations and conscious experience.

- On Left: Sensory Input (unconscious, unaware)

- Upper Arrow: Sense-making / Interpration / Locking Onto Meaning - “The brain locks onto and organizes a fragment of the visual stimulus; we are conscious of, and can report, this organization.”

- On Right: Conscious Experience (processed and interpreted input) - We experience only the results of brain computations, not the computations themselves. Our awareness is limited to the “shaded box” (momentary conscious experience). We do not have access to the raw sensory data (on left) or the underlying interpretative processes (upper arrow) that create our experience.

- Bottom Arrow: Shifting Attention: The brain struggles to disengage from its current organization and find a new one, allowing for dynamic reinterpretation (lower arrow). This constant movement gives rise to the illusion of a rich, detailed awareness of the world.

To quote: “This cycle is so rapid and fluent that we can have the sense of awareness of a complex object – or even an entire scene, in full detail and colour. Our stream of consciousness is of successive sensory organizations – consciousness is entirely confined to the shaded box. We have no conscious access to the information being picked up by our senses (the left- hand side of the figure) or how that information is interpreted (the curved arrows); or how our brain shifts to lock onto different information, e.g. by shifting our attention (with or without moving our eyes).”

Several key insights follow:

- Consciousness is superficial. To quote: “Each cycle of thought delivers a consciously experienced interpretation, but no explanation of where that interpretation comes from” (p 13). There is nothing more to the mind than the fleeting contents of our stream of consciousness. The only thoughts, emotions, and feelings are those that flow through our stream of consciousness. Consciousness is surprisingly sparse and is defined by the interpretations through which we organize sensory experience.

- The brain operates by precedents, not principles: Each new cycle of thought makes sense of information by reworking and transforming remnants of past related thoughts. The brain relies on past experiences rather than fixed principles.

- “These imaginative jumps are, I believe, at the very core of human intelligence. The ability to select, recombine and modify past precedents to deal with present experience is what allows us to be able to cope with an open-ended world we scarcely understand. The cycle of thought does not merely refer passively to past precedents – we imaginatively create the present using the raw materials of the past.” (p 203)

This cycle explains how our conscious awareness arises moment by moment, through the brain’s ability to organize sensory input into meaningful patterns while seamlessly transitioning to new interpretations.

Critical Questions and Areas for Further Exploration

Personally, I felt the book missed several key biological and mental health considerations:

Question 1: How does “nature” constrain change?

While Chater’s model leans heavily on nurture, it doesn’t adequately address the constraints of biology. For instance, how do epigenetics, genetics, and early environmental influences shape the mental “precedents” we can form? How does our “bounded rationality” interact with our “bounded biology” in shaping who we can become? While the book is optimistic about change, it leaves unanswered questions about the limits imposed by our biological inheritance.

Question 2: How does culture impact cycles of thought?

I appreciated Chater’s description of how perception and interpretation emerge, but the book misses an opportunity to examine the cultural and societal framing of thoughts, ideas, and language. Our thoughts don’t arise in isolation; they are deeply embedded in our cultural and social milieu. If we want to reshape our minds, how does our culture—shaped by the minds of others—support or constrain this process? Moreover, how does culture itself evolve through cycles of collective thought and reinterpretation?

Question 3: Evidence for the neural bottleneck in sensory processing and consciousness.

Nike Chater claims, “Consciousness, and indeed the entire activity of thought, appears to be guided, sequentially, through the narrow bottleneck: deep, sub-cortical structures search for, and coordinate, patterns in sensory input, memory and motor output, one at a time.” This suggests that consciousness and thought are constrained by the brain’s inherent processing limits, with deep brain structures playing a pivotal role in coordinating sensory inputs and outputs. For instance, sensory information is processed through specific pathways like the thalamus and cortical areas, while the prefrontal cortex integrates and prioritizes this information.

Research and subjective experience indicate that the brain operates under significant bandwidth constraints, particularly in conscious awareness. Our ability to consciously and attentionally multi-task is limited. Various attentional studies reveal that humans can only focus on a limited number of stimuli at once, suggesting a natural bottleneck in sensory processing.

Chater’s claim about the neural bottleneck provides a compelling framework for understanding the limits of conscious awareness, particularly the idea that deep sub-cortical structures prioritize and filter sensory input. However, while this model aligns with many findings in neuroscience (an area I’ll need to read more about), the evidence to support this seemed indirect and area I’d like to see more studies on.

Concluding Thoughts

“Yet if the mind is an engine of precedent, continually reshaping past thoughts and actions to deal with the present, then each of us is not just a bundle of character traits, but a rich store of distinctive past experience: we are like corals layered, polyp by polyp, into infinitely diverse forms.” (p 198)

The Mind Is Flat by Nick Chater is one of the more striking books I’ve read in recent years and my top “made-me-think” book of 2024. As an atheist and strict materialist, I’ve long believed we do not possess some inner self or soul. But I’ve struggled to articulate or explain some of the “magic” and “mystery” in our human cognitive experience. A strict reductionist view of the mind feels limited framework to formulate how our minds evolve and how the culture and our collective minds change.

This book challenges the very notion of what we often believe it means to be a self or human, and those critiques can be off-putting to us an individuals. It often feels easier to explain away our poor behavior or negative moods as “just the way we are” and avoid changing. Similarly the search for authenticity is often culturally framed as a quest for finding and following your “true self.” But if we accept Chater’s view of the mind as “flat,” we must reframe our understanding of selfhood and personal growth.

Chater’s metaphor of the mind as an “engine of precedent” offers a powerful alternative. Transformation isn’t about uncovering some hidden inner truth or self but about slowly remodeling the mind through new precedents. This is an idea that aligns with many of personal growth and self-evolution. Chater uses a vivid metaphor to illustrate self-transformation and creation of new thoughts and actions that get laid down layer by layer, like corals building their structure polyp by polyp. This metaphor resonates because it acknowledges our history while emphasizing the possibility for growth and change.

Ultimately, Mind Is Flat is an extraordinary read that challenges its audience to rethink their assumptions about the mind and to take a more active role in shaping the person and brain they wish to become.

Got a comment? Send me an email.

References:

Chater, Nick. (2019). Mind Is Flat: The Remarkable Shallowness of the Improvising Brain. United Kingdom, Yale University Press.