How to Track, Analyze and Understand A Life in Writing

“For years I have looked for the perfect pencil. I have found very good ones but never the perfect one. And all the time it was not the pencils but me. A pencil that is alright some days is no good another day.”

John Steinbeck, “Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters”

Can we track what we write? If so, how? And what can we use our writing tracking for?

As a self-tracker and an enthusiast of the data-driven life, I track a lot of my life, but as a writer, I find the tracking options rather limited. There are tools to log my writing time and how words I typed, but there is nothing that allows me to keep a complete history and data on all of my notes, drafts and final creations. I wanted a way to track what I write, not just my time or word count.

Fortunately, since I migrated off Evernote, I now write in plain text files. Plaintext files are a file format that is future-proof, flexible and portable. They are also trackable, and I am able to track my life in writing.

Using git, a popular way to manage software development, I have assembled a self-tracking method for keeping a complete history of my files, including each and every change I make, and for logging daily statistics on words added, files changed, and more. In short, with plain text files, git and a few automation scripts, we have a comprehensive and robust method of tracking our writings and notes.

In this post, I want to share how to track your writings. By using plaintext files, git and a few scripts, I’ll show what it takes to record a complete history of your notes into git and also collect some high-level statistics of daily changes. Since it is important to know what data we are getting and the potential insights we can get from the data, I’ve also provided a starting point for some data analysis on that tracking data.

Hopefully, by the end of this post, you’ll have mastered the basics of managing and tracking your writings with plaintext files and git and equiped yourself with a way to comprehensive way to track your writings and notes in the future!

NOTE 1: You can find the code for this post at Writing Tracker.

NOTE 2: For a more in-depth dive into writing and note-taking check out The Plaintext Life: Note Taking, Writing and Life Organization Using Plain Text Files, and for a step-by-step tutorial on migrating off of Evernote to plaintext files, see Post-Evernote.

Proxy Metrics: Writing Time and Typing Word Count

I’ll admit that I’m a pretty obsessive tracker. I’ve even gone so far as to track my poop (don’t judge before reading!). When it comes to writing, historically I’ve used a number of metrics to track my writing.

For example, using RescueTime, I track my computer time and my time spent in apps. This allows me to know what percentage of my time is on writing-related tools. Similarly, using Toggl time, I manually turn on and off a time tracker. This allow me to log how long I actively spend on certain specific projects, especially client work but also my studies, writings and organizational chores. Basically, I know how much time I spend on writing on my computer.

According to my 2018 data analysis, I spent 370 hours actively on writing, which was a 62% increase from the year before. This resulted in longer and better blog posts and considerable progress in my yet-to-be-published works. Here is a heat map comparing my writing time in 2017 vs. 2018:

One very noticable difference is that I have more days where I spent 4 hours or more writing in 2018. Most successful writers dedicate a period of 2-4 hours for their writing. I still find my writing routine somewhat inconsistent, but this is a step in the right direction.

While time logs are an interesting and important dataset for knowing if I’m sticking to my habit of writing, it is a proxy metric. It only measures the time I’m putting in. It doesn’t tell me much about my output, like how many words I type or what notes I worked on or the evolution of my corpus of notes and drafts.

When it comes to my written output, one way to track this is through how many words you type. For a couple years, I’ve recorded my creative typing number using a Mac app called WordCounter. This tool lets me track how many words I type per hour on certain designated programs (and exclude non-writing programs, like browser, email or a coding editor). This app doesn’t record what I type or in what specific document, but it does let me track how many “creative words” I type each day and using which applications.

Here are two examples:

On the left, we see the default stats provided in the menu by WordCounter, and, on the right, we see more advanced analytics provided by my Alfred Integration for WordCounter. This workflow includes a way to export your daily data and a couple data visualization reports.

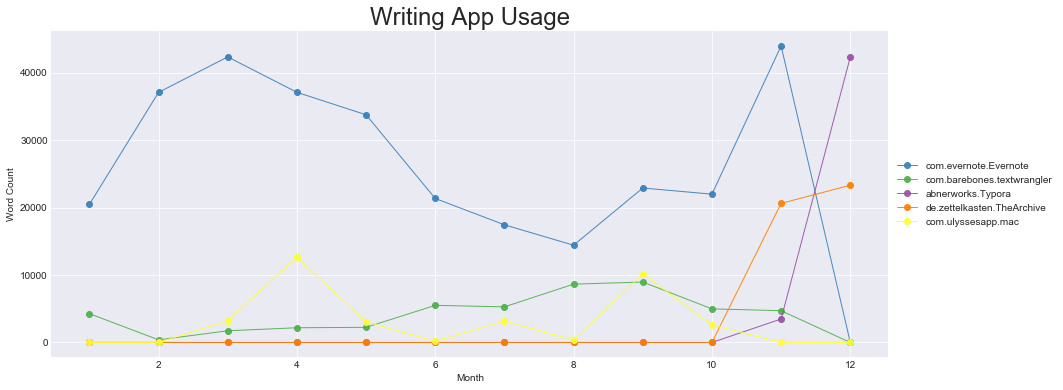

If you want to go even deeper, in my QS Ledger I’ve created a Data Analysis Jupyter Notebook on WordCounter. This script will extract your data and provide a number of ways to visualize it. Here is the changes of my tool usage in 2018:

This chart provides shows which months I was most prolific (May, Nov, and Dec) and the change from using almost exclusively Evernote and TextWrangler to my current tool stack of The Archive and Typora.

Overall, WordCounter is a great way to track my writing activity. It tells me how many creative words I write per hour and which programs. This allowed me in my year-in-review to see which , which days of the week I write the most (Monday and Wednesday) and even which hour of the day (10am and 11am).

While time logs and word count output are a pretty good start to tracking how much I write, it leaves a lot to be desired. Both are proxy metrics to what I’m actually trying to track and understand, namely my writing output. I could use a similar proxy metric like my Todoist log of writing tasks completed too.

Basically, time logs are a proxy to the eventual output since it tells me about the time I’m putting in, and my word count tracker is a proxy to what I eventually create as blog posts and book chapters. But neither really helps me understand the evolution and genesis of my actual writings. Neither provide as much data as should be possible if I want to have something like a life log of my complete writing life too.

In order to understand much more on my writings, we are going to need to start tracking my actual notes and writings!

Want to Track Your Writings? Write and Store Your Notes in Plaintext Files

There are a lot of tools out there for writing and note-taking. Most are full-featured apps that handle both the role of editing and organizing. These note apps can be pretty useful and convenient, but they come with a few limitations.

The biggest limitation is where your actual text gets stored. In nearly all programs, the notes you write are stored or locked inside the program and inputed into some propertary text format. This limits your ability to port your data other systems. Also, having the input in a non-standard format makes it hard to use it differnet mediums. For tracking purposes, this “locked in” aspect makes it almost impossible to get any data on your writings too.

In order to track our writings we are going to either need a program that does the tracking for us or get our writings in a file format we can track ourselves. As far as I know, none of the major note-taking applications, like Evernote, OneNote, or Keep provide accessible tracking data on your usage nor an easy way to track this yourself. So, for tracking purposes we are going to need access to file format that exists outside of the tool, and for us that means using plaintext files.

Plaintext files are one of the oldest file formats in computing and are the basis of most coding. The chief advantages of plaintext files is that you can open them anywhere, and they’re portable, future-proof, and trackable.

Basically, keeping your notes in plaintext files will never require a subscription, lock away features, or go out of business. It’s free and here forever. And you can choose from any number of tools to edit and manage your files.

So, if you want to track your actual writings and notes (and not just your writing time or global typing, word count), the best way to start doing this is to write and store all of your notes in plaintext files.

Now when it comes to the actual tracking, the best approach in my opinion is git. Git or more specifically git version control is the most popular method for tracking and managing code today. Much like how one can track code and software development, with plaintext files I can now track my writing and writing process too.

Let’s now to turn to setting up our writing tracker with git.

What is Git? Coder’s Friend for Tracking Your Files

In order to better understand and better track my writings, I needed to start tracking my actual notes, not just my time or my typing. Unfortunately, none of the major note-taking applications provide much tracking data nor make it easy to track your files. This is why for trackability it was necessary to keep everything in files. This make it possible to track changes using git.

Git is a distributed system for tracking changes in files. It was created by Linus Torvalds in 2005 to help manage the development of the Linux, an open-source operating system. It was designed for and is typically used by programmers to manage changes in code, but it can be used to track changes in any set of files.

Git works a bit like a filesystem in the sense that you store the latest version of the files, along with a log of changes over time. These changes over time are called diff’s and are the differences between two versions or commits in time. Using git, multiple people can work on the same pieces of code and later merge those changes together.

An intro to git goes beyond this post. There are a lot of great resources online for learning and installing git. Two I recommend are the Git Guide and Github’s Try Git. Installing and learning basic commands for Git should only take 30 minutes to an hour. Most git-related challenges you encounter can be solved through Google Search, StackOverflow, and try and error.

Once you have git installed, you are now able to track the changes to a collection of files overtime. Typically developers make manual “commits” as they work on the code. Basically once you’ve finished your work you save your changes into the git repository with a short log message. For example, “Fix for bug 123” or “Initial Work on Feature XYZ.” The commit history is a central feature of git since it provides a complete log of any and all code changes over time.

When it comes to tracking our writings, we can also use git. All you need is a directory of files. For example, each time you make changes, you can save and log them into the repository. This is how some writers use git.

But if we want to go beyond this manual process we are going to need to automate our notes tracking with git. This is why I created Writing Tracker, a git-based notes tracker and statistics counter.

How to Automatically Track Plaintext Notes with Git

NOTE: You can find the bash script code for this section at https://github.com/markwk/writing-tracker.

Writing Tracker is a collection of scripts for tracking and data analysis of writings or plaintext notes. My main goal and the goal of the project is to provide a simple tracking setup for any directory of plaintext files. In turn, I’ve included both a simple data report and a jupyter notebook for more advanced data analysis.

Writing Tracker has three main components:

- writing-tracker.sh: script to track daily changes in a directory of plaintext files

- report.py: simple python script to graphically plot latest stats with pandas and matplot

- writing_data_analysis.ipynb: Jupyter notebook in Python to analysis of writing stats.

In order to get started check out the installation and setup steps](https://github.com/markwk/writing-tracker#installation-setup-and-usage-writing-tracker-with-bash-and-git).

The core of the project is writing-tracker.sh. This is a bash script. A bash or shell script is a way to run a series of command line or terminal commands.

Basically, I’ve created an automated process to look first at the changes to your writing files directory and commit them to a git repo. The code then runs a series of calculations (new files, word count, etc) to see what changed. These stats are stored to a separate CSV spreadsheet file. Finally, the files changes are committed with a basic log message of the date and a few key statistics.

In the end, we’ve stored a complete history of these files and we’ve calculated a daily breakdown of noteable changes.

Let’s walk through what the script does step-by-step.

At the top of the script are a number of variables you configure for where your directory is and where to store your output statistics.

The first real step in the script starts with git:

# Navigate to target directory and start git staging

cd "$TARGET_DIR"

git add .

This adds all the files to the repo so we can parse the recent changes. We then run git status and use grep to extract and count the various file changes:

# File Counts

total_files="$(ls -1q * | wc -l | tr -d '[:space:]')"

files_changed="$(git status | wc -l | tr -d '[:space:]')"

files_added="$(git status | grep 'new file' | wc -l | tr -d '[:space:]')"

files_modified="$(git status | grep 'modified' | wc -l | tr -d '[:space:]')"

files_deleted="$(git status | grep 'deleted' | wc -l | tr -d '[:space:]')"

files_renamed="$(git status | grep 'renamed' | wc -l | tr -d '[:space:]')"

echo "Files: total files: $total_files, total changed: $files_changed, added " $files_added, "modified " $files_modified, "deleted " $files_deleted, "renamed" $files_renamed

Similarly we use git diff to parse and calculate word counts in those differences:

# Word Counts | Credit: https://gist.github.com/MilesCranmer/5c7d86c8740219355d2dfdb184910711

words_added=$(git diff --cached --word-diff=porcelain |grep -e"^+[^+]"|wc -w|xargs)

words_deleted=$(git diff --cached --word-diff=porcelain |grep -e"^-[^-]"|wc -w|xargs)

words_duplicated=$(git diff --cached |grep -e"^+[^+]" -e"^-[^-]"|sed -e's/.//'|sort|uniq -d|wc -w|xargs)

echo "Words: added " $words_added, "deleted " $words_deleted, "duplicated" $words_duplicated

Since I use tags and special reference keys, I do some specific checks to count those too.

# hashtag counts (note: excluding hashed tagged words like #1234)

hashtags_added=$(git diff --cached --word-diff=porcelain | grep -e"^+" | grep -o '#[a-zA-Z]\+'|wc -w|xargs)

hashtags_deleted=$(git diff --cached --word-diff=porcelain | grep -e"^-" | grep -o '#[a-zA-Z]\+'|wc -w|xargs)

echo "Hashtags: added " $hashtags_added, "deleted " $hashtags_deleted

# Count of citations references in special format like #123.

# Used in the case of a reference manager like Bookends or Zotero.

refs_added=$(git diff --cached --word-diff=porcelain | grep -e"^+" | grep -o '#[0-9_]\+'|wc -w|xargs)

refs_deleted=$(git diff --cached --word-diff=porcelain | grep -e"^-" | grep -o '#[0-9_]\+'|wc -w|xargs)

echo "References: added " $refs_added, "deleted " $refs_deleted

The final result is that I’ve recorded the daily changes overall and stored a few data points on what changed. For example, I’ve got data on how many files were added, changed, deleted, etc., and I know how many words were added or removed. Additionally, I’ve created some special commands to get more relevant data like number of tags added.

Once this is all completed, we run two more commands:

# Save stats as new line with date to local csv

echo ${YESTERDAY}, ${CURRENTDATETIME}, $total_files, $files_changed, $files_added, $files_modified, $files_deleted, $files_renamed, $words_added, $words_deleted, $words_duplicated, $hashtags_added, $hashtags_added, $hashtags_deleted, $refs_added, $refs_deleted >> $DATA_FILE

# Commit Changes to Git with Custom Message

commit_msg=("$YESTERDAY Daily Writing Stats: Words Added: $words_added, Files Added: $files_added")

echo $commit_msg

This puts the saved stats into a CSV file and commits all of the file changes into the repo with a short message.

Using cron, which I high recommend to anyone intending to use this, you can automate this script to run once a day, like midnight or at 1am. Techinically I could tweak it to run every hour, but once a day is fine for my purposes.

When it comes to tracking my writings, I think plain text files and git make for a robust and powerful approach. It also gives us a ton of data too. All I needed to do was automate it with bash and export the stats to a CSV.

Inital Data Analysis and Data Visualization of My Writings and Note-Taking

NOTE: You can find a Python Script and Jupyter Notebook for this section at https://github.com/markwk/writing-tracker.

Now that we’ve got our git writing tracker working and let it run for a few weeks or months, we should have some data to start looking at.

There are two ways we could do this data analysis: a git-based analysis or daily stats approach.

Since we have a complete history in git, we could use some git stats and git repository analysis tools. For example, Git Stats provides some cool visualisations for local git statistics, and Git Quick Stats gives a view into your commit history. Neither of these quite fit our needs but they do give an idea of what might be possible.

This git analysis approach would allow us to get a raw and complete look at the evolution of our notes respository. We could see specific changes in any file over time. This is definitely the kind of deep analysis I intend to do one day, especially towards my long-term objective to study the geneology of my creative ideas. For now, it’s a bit beyond our needs or what I want to look at in this post, but having this kind history is exactly why we are tracking with git.

Instead, we are going focus on using our daily stats file. This is a bit more high-level but it still gives us a new perspective on how and where you write.

As we looked at in the last section, each day our writing tracker script logs some data points in a CSV spreadsheet along with a git commit. This gives us a bunch of daily statistics we can use to understand our writings. This stats file can be used in a simple spreadsheet or a more complex data visualization tools like Google Data Studio or Python.

As starting point, I’ve created a file called report.py which allows for a quick bar chart visualization of my writings. Looking at the last 7 days, let’s compare three areas: my creative words typed (in blue) and my actual writing output of my notes and drafts (in green) and my project notes (in purple).

![]()

These reports quickly show there is a discrepancy between my total typing count and projects vs. writing notes. For example, in this sample data, I have a day where I mostly work on my projects and did no actual creative writings. So, while I did type, I didn’t type much in the way of creative writings output. It was all project-related. This was a gap I couldn’t see with just my word typing data.

In writing_data_analysis.ipynb, I’ve provided a starting point to a more expansive data analysis. I currently trackthree directories of files: my writings/notes, my coding notes and my project, notes., and the notebook examines changes in my writing output behavior over time, in particular the difference between file changes and words added in those three areas.

Here are two breakdowns:

![]()

![]()

These visualizations quickly highlight where my writing was focused more on project and where it was creative output. I can also see which days too. These patterns might be useful for seeing a day of the week effect or explore correlations with other aspects of my life, like sleep, exercise, and HRV.

Obviously these are pretty early results using my writing tracker, but I think it shows a lot of potential going forward as I attempt to peer deeper into the creative process both intellectually and with data.

The main thing to remember is that since all of these files and their changes are logged daily into a git we have a complete historical record of our note-taking and drafts. Everything has been tracked and stored. It thus becomes possible to minutely examine how an individual note, idea or draft evolves. I’ll be able to see how a cluster of notes on a certain topic emerges, becomes a draft and maybe eventually transforms into something larger, like a blog post, article or book.

Obviously it’s still early, but we have this power and potential since we are now tracking our writings using plain text files and git.

Conclusion: Steinbeck Cared About His Pencils, I Care About Tracking

As John Steinbeck was finishing one of his last masterpieces, East of Eden, he was still pondering his writing desk, his creative process, and even his preferred pencils (and their sharpness!). Steinbeck was one of the most well-known writers of the 20th centry and produced some of the most iconic books in American literature, and yet there he was thinking about his tools and tinkering with his workspace.

In Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters (1990), Steinbeck describes his creative journey, mental state and his wandering mind. He pursued a family life. He had hobbies like woodworking and an active interest in travel. In his late 40s at the time of writing that novel, he also still found time to “invent a paperweight for an inclined desk” and a “tool rack.” These are two of several instances where he discussed the physical tools and surfaces he worked on. In the often emphemeral realm of creativity, his journal entries remind us of how physical writing is, especially for pre-computer writers. It also show us how even successful writers and creatives still procrastinate and still think a lot about the tools they use to create.

Ironically, we find this procrastination/tool obsession in quite a few famous writers. It’s common for creatives to think about and even blame the tools we use, especially when we get stuck. It’s a form of procrastination but also a symptom of seeking improvements in the things we can control. Steinbeck cared about his pencils. I care about tracking.

In this post, we took a look at how to track your writings and notes with plaintext files, git and an automation script. We also briefly explored the data we collected and how to visualize and how it. While there might be other metrics and ways to track your writing, I’d argue that there probably isn’t anything more comprehensive and robust as tracking your writing history with git.

The end result of a git-based writing tracking method is that I’m now able to keep a complete historical log of everything I write, including drafts, smart notes, project notes and more. I now know how many words I added (or deleted) in a day on specific documents and any changes I make on an individual draft or note. Using a spreadsheet or a more advanced data analysis tool, I can visualize the evolution of a day in writing, a piece of writing, certain groupings of notes and much, much more. There is even the inherent potential here to provide a geneology of certain idea and whatever you end up creating from those initial fragments.

As a writer and software engineer myself, I often think about my tools, especially tracking tools. In lieu of actual writing, I can even can even become a bit too engrossed in my tinkering with my tools, management processes, and self-tracking. Fortunately I can take some degree of solace in writers like Steinbeck who also procrastinated, thought about his tools and even blamed his pencils!

As he puts it in a moment of writerly self-awareness:

“For years I have looked for the perfect pencil. I have found very good ones but never the perfect one. And all the time it was not the pencils but me. A pencil that is alright some days is no good another day.”

Creativity demands much of our minds but, it doesn’t require much in the way of tools, especially in writing. Steinbeck wrote mostly with pencil. The reality is that the tools are just a medium of creation, and most of us can get by on the basics of a simple computer or even a notebook and a pen. We shouldn’t blame the tools nor go on an endless quest from tool to tool. If you adhere to the concept of artist as craftsman, what matters is that you show up and do the work.

At the same time, assuming you are indeed doing the work, there is also nothing wrong with spending a bit of time on your tools and even a bit of “inventing,” as Steinbeck did. I think this is a case of needing space for both the work and the work about the work, which you might meta-cognition or meta-doing about the work.

Writer and professor Cal Newport embodies these two roles well. Newport is famous for his concept of “deep work,” which is the idea of removing distractions and finding focused periods of intense engagement. Newport has published both academic papers and mainstream books and exemplifies diligent output. At the same time, in his blog posts, I find elements of meta-cognition and the tinker. For example, in Plan.txt Newport recounts a simple way of managing his day-to-day, and, in Are you effective or just busy?, he challenges concepts of productivity and proposes a method called churn rate. Both posts show him thinking about how he works and “inventing” processes to make his work more effective, better organized and tracked.

I believe that when faced with being creative and innovative, tools we like and processes that fit how we like to work do matter. The right tools help us stay organized and in flow. I’d even argue that the right tools, habits and systems matter immensely in pursuit of organized, creative mind. Tinkering with your tools (or in my case tracking tools) also give us a beneficial way to “procastinate.”

Like Steinbeck, I shouldn’t blame my tools. As he put it, “it was not the pencils [to blame] but me.” All the same, even though we know it’s impossible to find it and eventually we must accept whatever works, it’s ok seek out the “perfect pencil” or whatever is your digital equivalent.

Best of luck and happy tracking!